We see bloodied figures and severed heads in the place of eroticising beauties.

Baroque art often confronts us with two particularly strong emotions: the terrifying and horror. Caravaggio and his successors chose tense moments in order to rouse these feelings in us, too.

They staged these moments in scenes that were consciously chosen to be confined. This draws us into close proximity with the scene. Illumination – spotlights and deep shadows – direct our attention so we do not miss any essentials.

We see bloodied figures and severed heads instead of eroticising beauties. Themes that are depicted time and again include Judith with the head of Holofernes and David with the head of Goliath.

These scenes had frequently been depicted before. Their intensity was new, though: Caravaggio‘s David is holding Goliath‘s bloodied head towards us in his outstretched hand. It is still disfigured by pain, frightening and horrifying us onlookers. Caravaggio‘s successors knew no mercy either.

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

(Milan 1571–1610 Porto Ercole)

David with the Head of Goliath

c. 1600/01

Poplar, 90,5 × 116 cm

Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum,

Inv. no. 125

Antonio d’Enrico, called Tanzio da Varallo

(Alagna Valsesia c. 1575/80 – c. 1632/33 Varallo Sesia)

David with the Head of Goliath

c. 1620

Canvas, 120 × 90 cm

Varallo, Palazzo dei Musei - Pinacoteca, Inv. no. 689

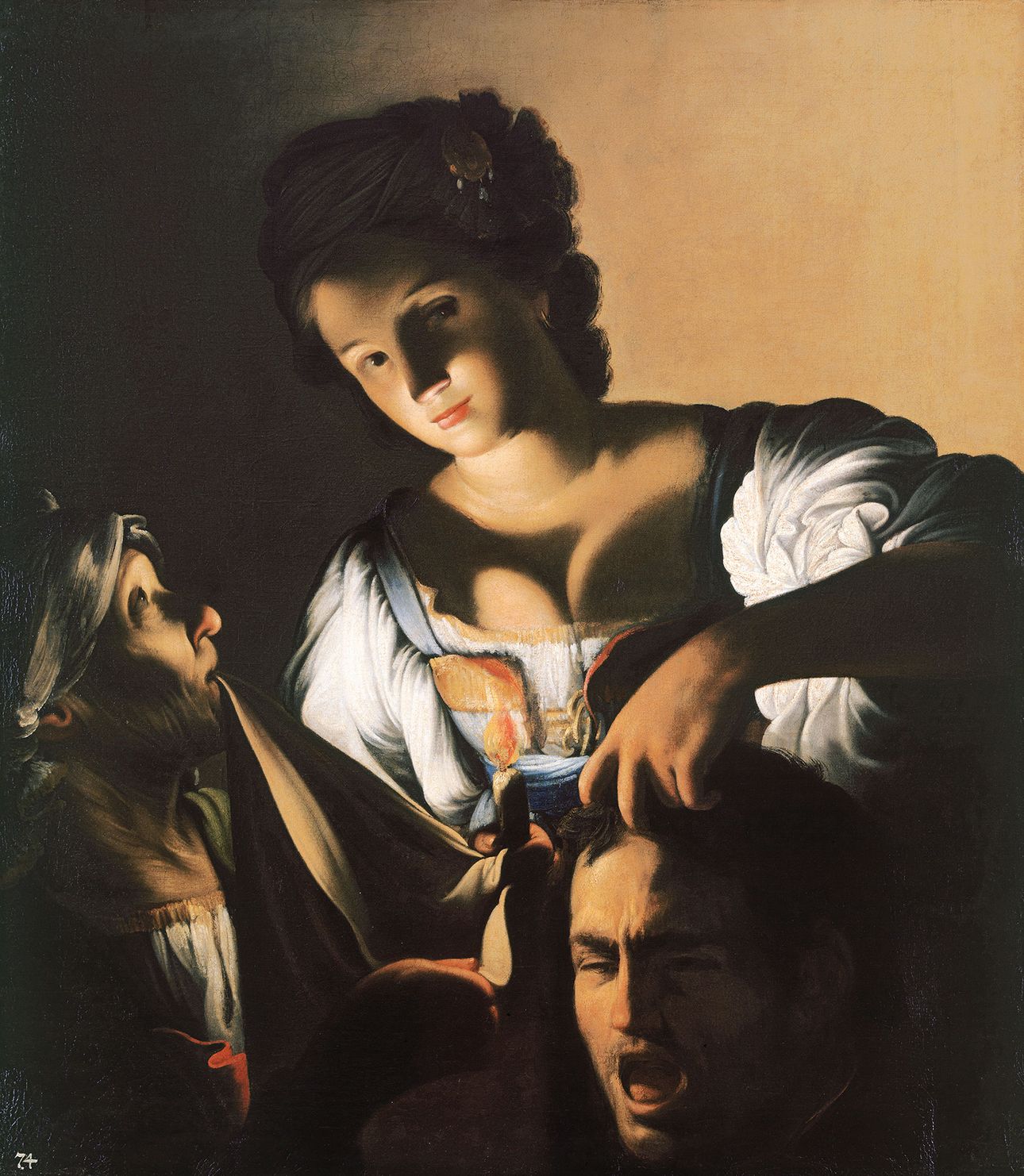

Carlo Saraceni

(Venice 1579–1620 Venice)

Judith with the Head of Holofernes

Um 1610

Canvas, 90 × 79 cm

Wien, Kunsthistorisches Museum,

Inv. no. 41

Horror and joy are not exclusive to each other in seventeenth century art, but in fact feed into each other.

Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna © Polo Museale dell'Emilia-Romagna

In Caravaggio’s time, works of art were not only evaluated by their ability to shock our emotions: paintings and sculptures were also judged by their truth to nature.

Aristotle‘s writings had regained popularity since the Renaissance. He described the joy triggered by recognition in us humans. It was therefore assumed that the enjoyment of a work depended on its truth to nature – even where the scenes depicted were anything but agreeable.

Horror and joy were not exclusive to each other in seventeenth century art, but in fact fed into each other. This is apparent from an extract from a poem by Giambattista Marino, a contemporary of these artists. He wrote in response to Guido Reni’s Massacre of the Innocents:

‘O noble artist, in cruelty still compassionate, well you know that even a tragic event is a precious subject, and horror oft-times accompanied by delight.’

Guido Reni

(Bologna 1575–1642 Bologna)

Massacre of the Innocents

1611

Canvas, 268 × 170 cm

Bologna, Pinacoteca Nazionale,

Inv. no. 439

It is not always easy to watch these scenes, even today. Even though we are exposed more than ever to terrible images, from the daily news and other sources, these works of art arouse feelings of pain and fear in us. This was the aim of Caravaggio and his successors: to trigger such strong emotions in us.